Are You More Driven by Inspiration or Outrage?

A Saturday Prompt

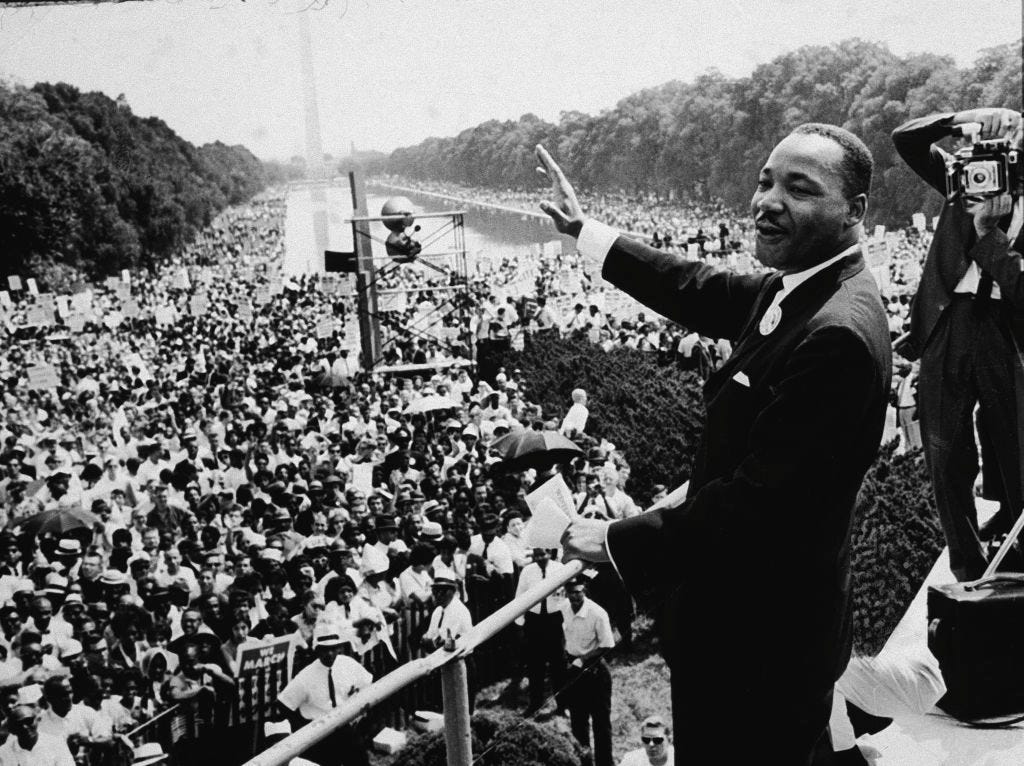

Two days ago was the 62nd anniversary of the March on Washington, a sunny day in 1963 when a quarter of a million people from all over the country descended on our nation’s capital. Most of us know that day because of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s impassioned “I Have a Dream Speech,” one of the greatest speeches in American history. Its words are resonant, inspiring and fueled by a fervor against injustice and inequality.

The day was officially called the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” and its purpose was to demand an end to segregation and to insist on voting rights, equal education, fair wages and basic civil rights protections. One leaflet urging people to attend said, “Go by plane, by car, bus, anyway you can get there—walk if necessary. We are pushing jobs, housing, desegregated schools.”

Coordinated by Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph and Martin Luther King in collaboration with civil rights, labor and religious groups, the day was defined by words and music. The youngest speaker was a 23-year-old John Lewis and the singers included Marian Anderson, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. Anderson sang “He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands,” Baez led the singing of “We Shall Overcome” and she, Dylan and Len Chandler sang a folk classic, “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.”

But the memorable centerpiece was King’s speech, delivered at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial. There’s no way to adequately summarize its full power, which is why I urge you to read or listen to the whole speech. But I’d like to touch on a handful of moments to highlight both its power and its combination of inspiration and outrage. Known as the “I Have a Dream” speech, the “dream” passage remains deeply touching:

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of "interposition" and "nullification"—one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

King’s rhetoric does not soft-pedal. He doesn’t hesitate to squarely confront injustice and oppression and the racists who support it. But he also allows us to imagine with him a better world. We can experience this combination of outrage and inspiration—its confrontation with an intolerable reality and its articulation of hope—throughout the speech.

King begins by remembering President Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation 100 years earlier. “This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice,” he told the crowd. “It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.” And then he shifts:

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

King also spoke about the promise of the Declaration of Independence—”that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’" Noting the nation’s failure to deliver on that promise, he said, “Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’"

Then he returned to hope: “But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we've come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

I’d like to share one more passage, when King memorably discussed “the fierce urgency of now” and insisted “this is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.” He called that approach fatal for the nation. His next words were a warning for those gathered—and its a message for all of us now who are suffering discontent and yearn for change:

This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

Let’s say it again: The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

In our day, the forces of oppression and injustice imagine that they represent the whirlwinds of revolt, but we know they are not inspired by the light of justice. Quite the contrary. But a central question is whether enough Americans who believe in democracy and reject authoritarian rule will revolt—will gather together and demand change. And, what it will take to get there.

So, today’s prompt: Are you more driven by inspiration or outrage? Are you more moved by MLK’s hopeful vision or activated by his fierce articulation of what’s wrong and must change? Are you more likely to join public protests or other gatherings based on particular issues that outrage you or be called to action by a hopeful envisioning of what King called “the bright day of justice”? Please do share specific issues that you think may catalyze change now, such as rising prices, kidnapping of migrants and other people of color, and deployment of military troops in our cities.

As always, I look forward to reading your observations and the opportunity for this community to learn from each other. Please do be respectful in your remarks. Trolling will not be tolerated.

America, America depends on reader support. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber for $50 a year or just $5 a month, if you’re not already. This helps sustain our work, keeps nearly all the content free for everyone and gives you full access to our dynamic community conversations.

I am driven by both inspiration and outrage, and believe that both are necessary to fuel the Resistance.

I think both. I am an elderly (72) white woman born and raised in the South. MLK Jr was killed in my hometown when I was 15. Today I see people snatched off the streets of America by people who won’t show their faces. We have a cancer in our government that’s trying to destroy everything we’ve been about for the last 250 years. I’m both inspired and outraged. And I will not go down without a fight. At my age I’m more than willing to give my very life in sacrifice for my country.