NATO Ally Finland Takes Center Stage

With President Biden in Helsinki, the formerly neutral Nordic nation turns the page on its historic relationship with its neighbor Russia

The Beast, the 18-foot, armor-plated, bulletproof presidential limo—complete with tear gas grenade launchers, night vision cameras, satellite phone and a refrigerator with blood matching President Joe Biden’s blood type—arrived in Helsinki on Monday. This was three days before Biden flew in yesterday from Vilnius, Lithuania, and the NATO Summit.

The decked-out Beast was just one of literally thousands of details involved in planning a foreign visit by an American president. An estimated entourage of 600-700 not only joined him in the Finnish capital, some had arrived weeks or even months in advance to make sure nothing would go wrong. He was there to celebrate Finland’s ratification as a NATO member—the “fastest in NATO history,” Biden told Finnish President Sauli Niinistö Thursday in opening remarks—and to confer with other Nordic friends, including the soon-to-be NATO addition, Sweden, now that Turkey has withdrawn its opposition to the country’s membership.

The day before, Biden concluded the larger summit with an address at Vilnius University, underscoring his optimism and belief in “democratic values we hold dear.” He said, “NATO is stronger, more energized, and, yes, more united than ever in its history,” then added, “It didn’t happen by accident. It wasn’t inevitable.”

“After nearly a year and a half of Russia’s forces committing terrible atrocities,” Biden continued, “including crimes against humanity, the people of Ukraine remain unbroken…Ukraine remains independent. It remains free. And the United States has built a coalition of more than 50 nations to make sure Ukraine defends itself both now and…in the future as well.”

It’s a message that Niinistö picked up at the closing press conference in Helsinki. “We will continue to support Ukraine,” he said, which is “not only defending itself, but all the values that represent the Western world.” And what of Finland, which Biden called “a strong, vibrant” nation? Biden got the last word: “What I think Finland joining NATO does…it just makes the world safer.”

What a difference five years makes. The last time a US President was in Helsinki, almost exactly five years ago, Donald Trump betrayed his country and its 17 intelligence agencies by siding with Russian President Vladimir Putin about Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election. "President Putin says it's not Russia,” a beaten-looking, traitorous Trump said after emerging from a private meeting with the Kremlin boss. “I don't see any reason why it would be.”

That day, July 16, 2018, was a sad and disgraceful day for America.

But it was also a difficult day for Finland, placed between Trump and Putin and its own commitment to American-inspired democratic values. It was one more milestone in its sometimes treacherous, sometimes supportive, but always complicated relationship with its eastern neighbor throughout the two countries’ long shared history.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of Finland joining NATO (it was ratified as the 31st member country in April). Not only does this Nordic country’s partnership more than double the NATO border by adding 832 miles, it means that Finland has profoundly turned the page on its relationship with Russia.

From an American perspective, the issue may be all about NATO unity and the opportunity to strengthen its position in support of Ukraine and the ongoing war with Russia. But for Finland—which requires mandatory military service and boasts a wartime force of 280,000 soldiers—this is also a moment to assert its independence from Russia and determination to secure its sovereign future.

“Security and stability are those elements which we feel very strongly,” Niinistö said in April. “If people can live in secure, stable circumstances, that's the basic element of happy life."

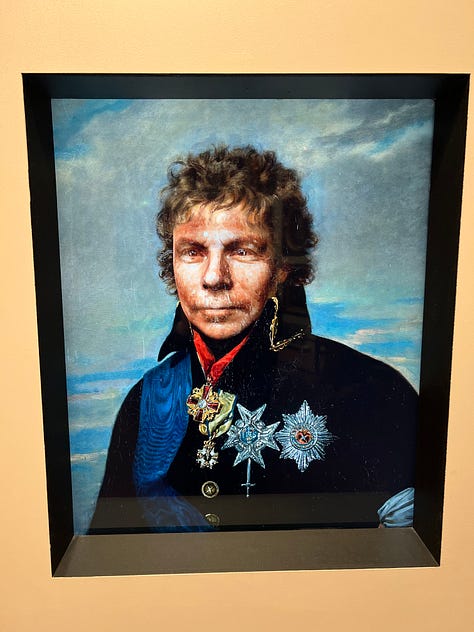

Let’s go back: Finland gained its independence little over a century ago. It was an autonomous duchy of the Russian empire from 1809 until 1917, when Finland’s parliament passed a declaration of independence and Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin and his government granted this change. From central architectural landmarks to street names and even public statues, Russia’s presence can still be seen. Helsinki’s Senate Square, for example, includes a statue of Alexander II (known as “the good tsar”) erected in 1894, is bordered by Aleksanterinkatu (Alexander’s Street) and has served as a stand-in for St. Petersburg in such films as Warren Beatty’s Reds.

Less visible but still real: A deep and decades-old cynicism toward Russian intentions, lingering from the deadly effects of the Winter War (1939) and Continuation War (1941-1944), when Finland lost some 90,000 soldiers in its ultimately successful effort to push back Soviet forces (whose casualties were significantly higher). There’s a not-so-funny Finnish saying (translated here) that exemplifies the hard feelings: You can sauté a Russian in butter, but they’re still a Russian. Finland’s alliance with the Germans during WWII represents one of the war’s more complicated arrangements as the Finns sought to hold off the Soviets and maintain their independence.

Still, in the subsequent post-war decades, my own gathering of anecdotes suggests that many if not most Finns did not fear Russian aggression—an interesting contrast to the Cold War fears that permeated American society. That mindset was surely aided by the strong hand that Finnish President Urho Kekkonen kept on Finnish society.

President from 1956 to 1981, Kekkonen’s “cigar-and-cognac diplomacy” involved visiting the Soviet Union more than 100 times; ensuring that Finland repaid war reparations through the development of large, state-owned enterprises; and providing a buffer between East and West by maintaining a low profile and resisting policies that may inflame Finland’s dangerous neighbor—an approach that came to be known, often critically, as “Finlandization.”

Here’s how I described it in 1994, several years after the collapse of the USSR on Christmas Day 1991, in a “Helsinki Postcard” entitled “The Thaw” for The New Republic. This was at a point when Finns had begun to question whether their leaders had gotten too close to their Soviet “friends.”

These are uneasy, painful times for many Finnish politicians, especially those who allowed the Soviets to exercise considerable influence on officially neutral Finland's foreign and domestic affairs…Now that the Eastern bloc has collapsed, the criticism is coming from within. Last year the Finnish press documented the money flow from the Soviet Communist Party to the Finnish Communist Party, the hard-drinking junkets taken by various Finnish parties on the Soviet tab and even speeches by Finnish politicians that were written with Moscow's input.

I opened that article with the story of Matts Dumell, who was convicted of espionage and jailed in 1984 for passing letters from Denmark to a Russian “friend.” I described meeting Dumell in a Helsinki café like this:

He blushes, laughs, nervously squeezes an empty wrapper for a last cigarette. Not because he thinks he was guilty of espionage, but because he believed that honesty was the best policy when police arrested him. He also believes that what he did by no means distinguishes him from dozens, probably hundreds, of other Finnish journalists, artists and politicians who regularly traded information, gifts and favors with their Soviet contacts.

But by the early ‘90s, a different gust of wind was blowing across Finland, well, at least in Helsinki. There was hope, like in many other capitals, that maybe, just maybe post-Soviet Russia would usher in democracy and a more constructive role for Russia in the Western world.

That feeling seemed to permeate a concert held in Helsinki’s Senate Square in June 1993; that event was quite improbable to imagine just a few years earlier. Permit me to quote from my article three decades ago:

Last summer 50,000 mostly young people jammed into Helsinki's cobblestone Senate Square for an ironic consecration of the Cold War's demise: Amid potted palms, the former Soviet Red Army choir came to play and sing with the Leningrad Cowboys, a Finnish rock 'n' roll band that sports comically exaggerated pompadours and wears mock military uniforms. To the embarrassment of many older Finns, the young Finns and old Soviets joined voices for such buoyant anthems as “Happy Together” and “Those Were The Days” (and, in a festive nod to America, “California Girls”).

This, of course, precedes the period when Russian president Boris Yeltsin handed over the country’s reins to former KGB agent Vladimir Putin, who prospered during the Soviet years and clearly clung to the belief that those days were better—that a return to Russian glory depended on reassembling a collection of former Soviet republics to reinstate its empire. That misbegotten world view has tragically led to war in Ukraine and genocidal levels of bloodshed, criminality and destruction.

That misbegotten world view has also motivated Finland, once disapproving of the idea of joining NATO, to now be a critical partner. Before the attack on Ukraine, most Finns had long opposed NATO membership. But in the first months after the invasion last year, public support grew from 53 percent (February) to 62 percent (March) and 76 percent (May). As one Finnish friend, who previously opposed NATO membership, told me a year ago: “When I understood that the Russians were shooting schools and hospitals, I understood there are no rules with them.”

The days when Finland rode the fence—defining itself by its ability, if not necessity, to straddle both sides—are over. “We stand at an inflection point in history,” Biden said, adding, “We want the people of Finland to know the United States is committed to NATO, committed to Finland, and those commitments are rock solid. We will defend every inch of NATO territory and that includes Finland."

I would be remiss not to share a few other images from my time in Helsinki, as promised.

America, America is sustained by paid subscriptions, making it possible to keep nearly all the writing available for everyone. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, please consider becoming one.

Aaah, an American president, a REAL president, in Helsinki actually defending America and democracy. How refreshing!!

Now we can toss the hideous terminology "Finlandization" into the dustbin of history, yes?