Reflecting on First Principles

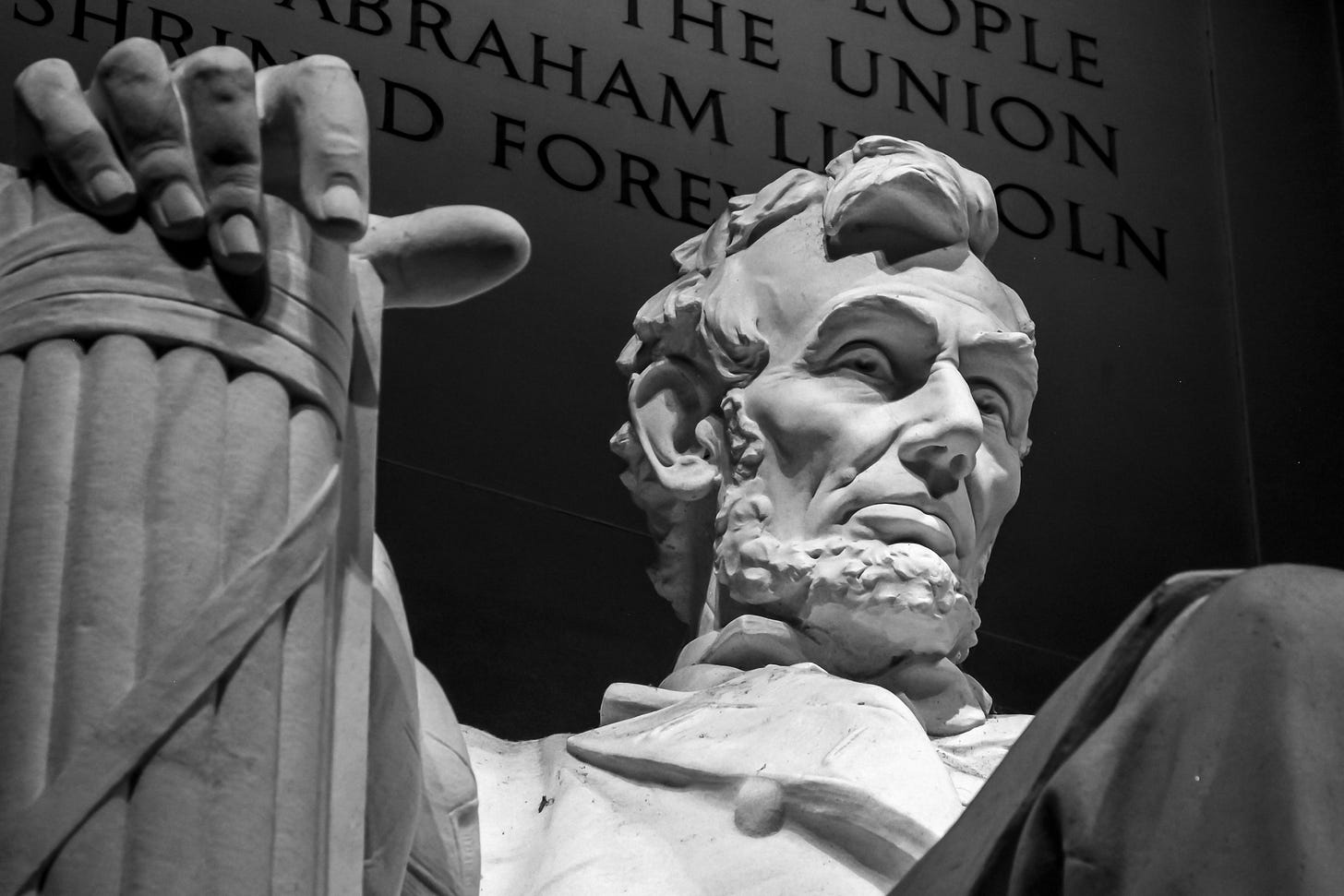

In the day before the midterms, what can we learn from Abraham Lincoln about the nation we want and the great task that lies ahead?

After the Battle of Gettysburg, the bloodiest of the Civil War with over 51,000 casualties of Union and Confederate soldiers, Gen. Robert E. Lee retreated back south of the Mason-Dixon line. The Confederate wagon train was said to be 15 to 20 miles long, filled with over 18,000 wounded soldiers. Left behind were nearly 4,000 dead, buried in shallow graves, and over 5,000 other soldiers missing or captured. The total casualties exceeded 28,000, nearly matched by Union casualties of over 23,000 soldiers.

President Abraham Lincoln stepped onto the blood-soaked grounds to dedicate the Gettysburg Civil War Cemetery barely four months after the devastating battle in July 1863. He did not use that sad day to expand the enmity between the states, highlight the horror of the South’s incomprehensibly deadly rebellion, unleash additional fury, or lash out to blame and demean those who had brought the country to that calamitous moment.

Rather, in a mere two minutes, President Lincoln aimed higher, extolling the virtues rooted in the Declaration of Independence, what he saw as the fundamental document defining the nation’s promise. His opening words, delivered before a crowd estimated at 15,000, gave voice to that essential idea intended to define and bind the nation and its people: “Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Then, Lincoln shared his vision of the republic’s democratic enterprise that had not yet been fulfilled and was now engaged “in a great civil war”—a test of whether “any nation so conceived…can long endure.” Despite all the bloodshed, all the shallow graves, all the violent conflict that was still underway, he did not hesitate in asking every American to consider the consecrated ground upon which he stood and the profound responsibility that lay ahead.

“It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

In this day before the 2022 midterms, after six years of metastasizing toxicity and division in which the idea and the ideal of democracy have been under attack and political violence has been exalted, Lincoln reminds us that the nation’s noble work remains unfinished, if all the dead and devoted “shall not have died in vain.” He reminds us that the great task of self-government and the challenge defined in the Declaration of Independence—“that all men are created equal”—remains for all of us to fulfill.

In his 1858 speech on the Fourth of July, Lincoln articulated what connects every American with the founding fathers who signed the declaration in 1776, which they began with the self-evident truth of equality: “That is the electric cord…that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.”

As Gary Wills noted, in his masterful Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, “Since the Revolution was not completed when national independence was won, its idea still faces people as a promise unfulfilled.” He continued:

They did not accomplish the political equality they professed. They did not end slavery. They did not make self-government stable and enduring. They could not do that. The ideal is not captured at once in the real.

Reflecting on the closing words of the Gettysburg Address, Wills describes Lincoln’s attachment to the Declaration of Independence as “an instrument of spiritual rebirth,” noting that “the spirit, not the blood, is the idea of the Revolution.” And the “great task remaining” at the end of Lincoln’s address “is not something inferior to the great deeds of the [founding] fathers. It is sad the same work, always being done, and making all its champions the nation’s permanent ideal.”

A year ago on January 6, we heard a lot of troubled talk about who are “great patriots.” We could see how many were willing to violently toss aside the sacred act of the peaceful transfer of power after more than two centuries. That misbegotten spirit, grounded in blood and the desperation to hold onto power, laid waste to the democratic idea extolled by America’s greatest president and the founding fathers.

Too many remain entranced by the dark vision that would end self-governance, concentrate power in the hands of the few—and usher in a dangerous form of despotism about which George Washington warned in his Farewell Address: “The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual” who will exploit this “elevation on the ruins of public liberty.”

Tomorrow we will begin to learn what nation most Americans—at least those who vote—seek to realize in the months and years ahead. Whatever the outcome, the great task of completing the unfinished work of democracy will remain before us.

If you find value in this writing, I hope you will become a paid subscriber to sustain the effort.

And in either victory or defeat tomorrow, as in July of 1863, the work ahead will include a continuation of the fight to preserve the progress already made real as we seek to inch ever closer to the ideal.

We mustn’t lose heart if tomorrow’s gains are small or altogether unrealized. And we mustn’t grow complacent if we manage to win the day. Regardless of the midterm battle’s outcome, the war for the soul of this nation is far from over.

JFK, another President of great significance once said: “Belief in myths allows the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.” While this can be true of both sides of our current great divide, untethered reality does seem to be prevalent on only one side.