What’s Left Out of the Story

Lessons on responsible storytelling from Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer," Florida's curriculum and immigration

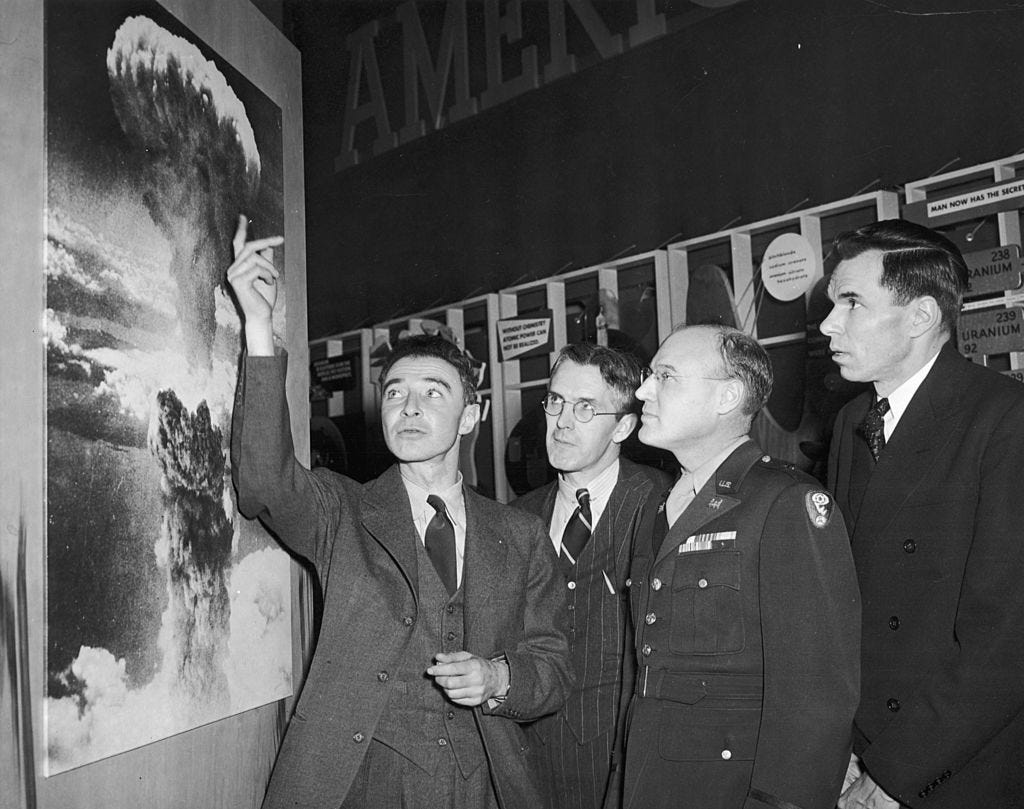

Count me a fan of Christopher Nolan’s new biopic, Oppenheimer—the writing, the directing, the acting, the brilliant telling of theoretical physicist Robert J. Oppenheimer’s growing moral conflict even as he believed in the necessity of building a bomb that could beat the Nazis and possibly end WWII. This is a genius director at the top of his craft with gifted actors able to bring this story to life.

But the more I’ve reflected on it, the more I’ve wondered about what Nolan chose to leave out. It’s hard to grasp or depict the scale of horror wrought by the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not only the death and destruction but the lingering physical and mental damage to the lives of hundreds of thousands of humans.

Yes, he spotlighted Oppenheimer’s understanding of the profound consequences of the atomic bomb—”Now I become death, the destroyer of worlds,” he quoted from the Bhagavad Gita. He featured the terrible conversation about how many tens of thousands of civilians could die if a bomb is dropped over a Japanese city. But he chose to skip images of the dead and dying and linger instead on Oppenheimer’s personal struggles and political confrontations with a McCarthy-era government questioning his Communist acquaintances and his own ideological inclinations.

Despite the tense, taut, carefully constructed scenes portraying the Manhattan Project’s Trinity Test—the first detonation of an atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert that was felt 100 miles away and sent a terrifying mushroom cloud 38,000 feet into the sky—the radioactive impact for the local population was ignored. (It’s a source of disappointment for survivors who were living within the bomb’s radius and their descendants, many of whom have dealt with high levels of cancer.)

Fair enough. This was Nolan’s choice. One film can’t do everything. And it was impossible to miss, throughout Oppenheimer, the profound and continuing existential danger the “Father of the Atomic Bomb” has wrought. No wonder the film’s three hours grab you and rarely let go.

But the question of where a storyteller should aim their lens—what to include and what to exclude—feels increasingly urgent when considering our current body politic. What is left out is often a more important indicator of a narrator’s intentions than what’s left in.

Much controversy has rightly been caused by Florida’s revised curriculum that requires instructors to teach middle school students that “slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

In this telling supported by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, teachers may minimize the horrors—the violent kidnapping of humans from their home countries, the torture and destruction of families, the theft of their freedom, indeed their very lives. Instead, why not focus the story on the skills learned that newly freed slaves could take into their post-slavery lives. Lucky people, huh?

(Confronted by a fellow Republican, DeSantis pushed back: “Are you going to side with Kamala Harris and liberal media outlets or are you going to side with the state of Florida?”)

This is all a piece of the effort to deny Florida students—all Americans if he gets his chance—the ability to know the truth of American history. As if young people can’t handle the truth. As if the sensitive constitution of white people will be crushed by the knowledge that their forefathers engaged in the practice of slavery. As if the only way to envision the future—one in which a shrinking white majority recognizes the day is coming when it will be a minority—is to deny knowledge and protect against minorities questioning their treatment, then and now.

We are not to blame! You have no right to make us feel bad! Look away! We’ll tell you another story.

This question of what to include and what to exclude is also on my mind whenever I write about America’s history of immigration. I’m always moved by the fundamental, inspiring story of immigrants who came to America to participate in the American project. There are so many touching stories of new Americans who faced extreme hardship and applied their talents to support their families, make new things, overcome prejudice and help build a young country searching for its identity.

But as compelling as these American stories can be—tales of millions of immigrants who have created a land of extraordinary diversity and possibility—we cannot avoid the fact that millions of African-born Americans were stolen from their lands and brought to America by force and an estimated population of 12 million Indigenous people died from genocide, war and disease between 1492 and 1900. (Some estimates are much higher.) To say the least, these are facts that complicate the story of immigration, indeed tarnish the easy inspiration experienced when ignored.

It would be simpler for white America to say once again: We are not to blame! You have no right to make us feel bad! Look away! We’ll tell you another story.

Every time you read, hear or see a multifaceted story that is rife with injustice and suffering but somehow leaves out the truth of the people who were harmed, consider that the storyteller may be consciously attempting to ignore the painful truths to keep you ignorant or, arguably worse, indifferent.

The first inaugural address of Barack Obama may seem like a lifetime ago, but recall the newly elected president’s words of encouragement, delivered on January 20, 2009.

On this day, we come to proclaim an end to the petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn-out dogmas that for far too long have strangled our politics. We remain a young nation. But in the words of Scripture, the time has come to set aside childish things.

How far we’ve traveled from those days when such healthy urgings lifted the body politic.

Even if Christopher Nolan chose to keep the lens trained away from the physical horror that continues to touch individual lives, I praise his creative achievement for motivating us to set aside childish things and engage the existential dangers still facing the human species.

It’s my belief that the advance of civilization depends on soberly confronting our history in all its complexity. Only by confronting hard facts is change truly possible. This is the sign of a mature society capable of taking responsibility and learning from the past. This is the path to real progress.

America, America is sustained by paid subscriptions, making it possible to keep nearly all the writing available for everyone. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one.

Very good. I've stood inside:

The gas chambers at Auschwitz

The bomb bay of Enola Gay

The actual Trinity site

The Ground zeros of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

I worked a bit for Phillip Morrison. He set the trigger at Trinity.

I have an SB Physics.

I've talked with Paul Tibbets and Chuck Sweeny

I knew about the Holocaust in 1965, age 11

I didn't learn about the horror of slavery in WVa schools. Not until about 1972 on my own reading

A few points:

1. Only knowing the horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki prevented (so far) World War III. Testing and demonstration never deter. The world detonated 450 Megatons in the air from about 450 nuclear blasts. Obviously, the radiation sickness and health effects were not a deterrent.

2. The Horror of the Holocaust is well known. It is to be taught in the racist Florida curriculum. Torture, death explained. The Horror of the atomic bomb is widely known. And why it was unnecessary to show it in Oppenheimer.

3. Too many white Americans, like Ron DeSantis and the illiterate Moms for Liberty are afraid of the historical truth of Slavery in America. Many adults know that Torture, Rape of women and children, lynching, hound chasing and more were all a vital part of American history. Lincoln estimated the wealth value of slaves in 1858 to be a then $1 billion.

4. There is no reason that Slavery Horror can't be taught along the same model of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.

I use this illustration. "The Germans taught the Jews good skills and provided good jobs that benefited them".

Outrageous of course. Like Florida's aversion and misrepresentation of Slavery.

Free articles on the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer from physicists who were actually a part, even Oppy articles, you can read them here:

https://thebulletin.org/2023/07/a-manhattan-project-historian-comments-on-oppenheimer

Sadly, many still are largely children. They want fairly-tales, mommy/daddy, and Big Brother. Laying off responsibility to someone else. As day-to-day life becomes more difficult for so many, it seems like an attractive choice. It seldom is.